Why Albuquerque Rapid Transit is far from a “Lemon”

by Jordon McConnell

About the author: Jordon McConnell, a nonprofit healthcare and education professional with a background in humanities and French, channels his passion for French urban planning to reimagine Albuquerque’s urban form. His unique perspective emphasizes equitable and holistic community development, aiming to enhance the city’s quality of life for all.

In 2011, the City of Albuquerque began studying the idea of implementing a bus rapid transit (BRT) system along Central Avenue. Bus rapid transit is a form of mass transit that can vary in look and implementation, but generally requires level-boarding platforms for buses, off-board fare payment, dedicated transitways, and signal preemption at intersections (giving buses priority for green lights). By 2016, this idea was put into action, becoming the Albuquerque Rapid Transit (ART) project. The City sought to replace the aging Rapid Ride system with a better experience, improving passenger comfort, safety, speed, and reliability on the system while also encouraging new, denser development along one of the city’s main thoroughfares.

The project proved to be controversial and lawsuits attempted to block ART, but construction began in earnest in 2016. At the end of construction, the city had a pair of rapid transit lines running 12 and 14 miles respectively, including 11 miles of shared, dedicated transitway. The system featured enough of the attributes of a true BRT that it was awarded the first Gold-Level service standard in the United States by the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy. Controversy continued after its initial opening, as buses provided by BYD Industries proved unable to service the ART routes, causing the system to be delayed. By 2019, the City procured new replacement buses and put the system into regular operation after a two-year delay. In its first few months of service, before the COVID-19 pandemic, the ART succeeded in surpassing the old Rapid Ride’s ridership by over 30%.

Despite this, in 2018, Mayor Keller infamously stated that ART was a “bit of a lemon.” This is a sentiment still felt by many Burqueños, some of whom feel that the project was a waste of money, poorly executed, or unnecessary. Is ART, in fact, a waste? Or is it an essential and successful piece of transit infrastructure and a catalytic part of the city’s urban history?

In a solid rebuke to the project’s detractors, including the Mayor, ART is actually exceeding ridership expectations despite the after-effects of the pandemic and shows a path forward toward a more urban, more equitable, and lower-emission Albuquerque. While concerns about the project’s initial design and implementation are valid, it is important to acknowledge the game-changing nature of ART and the long-term benefits it can bring to Burqueños.

Why Was ART Built When the Rapid Ride Was Already There?

A common view held by detractors is that the ART project was redundant or unnecessary as the previous express bus system on Central Avenue, the Rapid Ride service, was adequate. Let’s address this first. Though the system had “Rapid” in the name, it was a misnomer, as the Rapid Ride failed to accomplish the goals of a true rapid transit system. ART, however, was designed to complement the urban fabric of the corridor while enhancing and providing a more advanced, faster, and more efficient transit option along the corridor.

As Albuquerque continues to evolve into a medium-sized metropolis approaching a million people, investing in rapid transit is not just a matter of convenience but a strategic necessity. Rapid transit projects like ART play a pivotal role in addressing the escalating challenges posed by traffic congestion, air quality, and the demand for more sustainable transportation options. By embracing efficient and environmentally friendly transit solutions, Burqueños can ensure that our transportation infrastructure aligns with our city’s growth trajectory – fostering economic development, reducing urban sprawl, and enhancing the overall quality of life for residents. In this context, ART can do what Rapid Ride simply could not.

Here’s the context:

The Rapid Ride had lower frequencies than what we enjoy with ART. The best frequencies enjoyed on Rapid Ride (every 15 minutes for each line, or about every 8 minutes where they shared their route), are the minimum frequencies for ART on weekdays. For those of us who routinely used the Rapid Ride to commute, these frequencies were rarely actually the case, with buses often delayed.

A large part of ART’s success is due to its dedicated busway, which Rapid Ride lacked. The frequency of Rapid Ride was often worsened by interactions with traffic congestion. This led to “bus bunching,” where a bus falls behind schedule while the next bus catches up to the delayed bus, leading to a situation where both buses arrive at the same stop close together or at the same time. It was not uncommon for bus bunching to cause up to 40-minute delays on Rapid Ride buses! In addition to traffic congestion, this phenomenon could be caused by passenger boarding and disembarking. At busy stops such as Alvarado Station (especially after a Rail Runner train arrived) or UNM at Central and Cornell, buses were often held up for as long as ten minutes while large numbers of passengers boarded the bus and paid their fare.

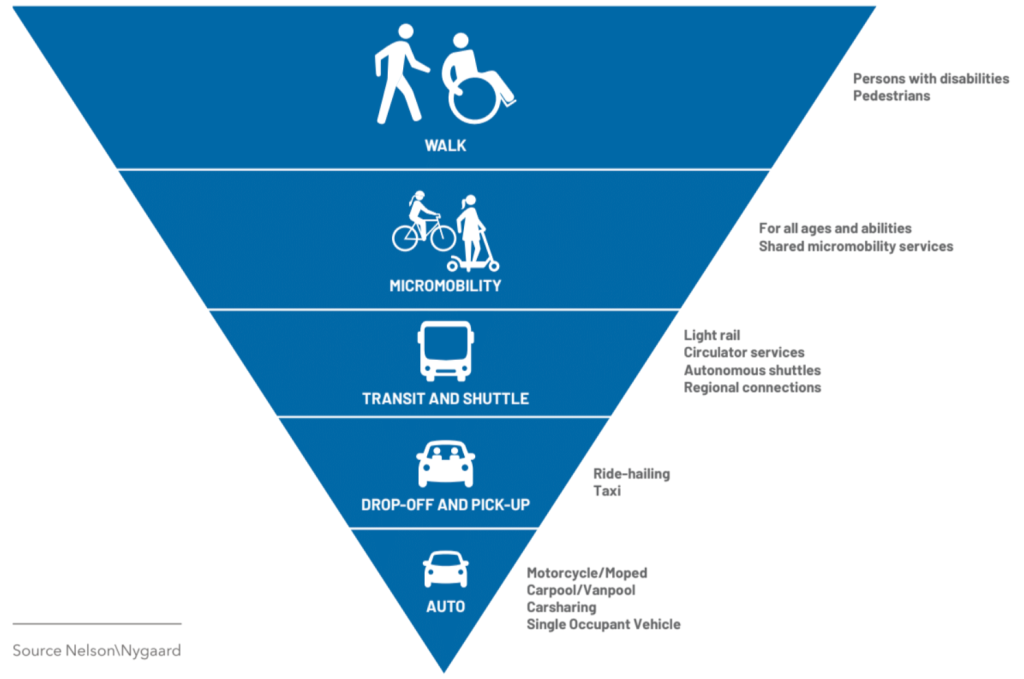

As a BRT system, ART was designed to offer even greater efficiency and quality of service compared to traditional bus systems (including the Rapid Ride), by incorporating dedicated bus lanes, modern stations, signal priority, and other features. In allowing vehicles to bypass traffic congestion as well as allowing passengers to board the bus at all doors, ART was designed to stay on schedule and deliver a better experience for passengers. In addition, the level-boarding enabled by the station platforms also allows for faster boarding for folks who use mobility aids, such as wheelchairs, as well as families with strollers, bicycles, and other wheeled devices.

Another complaint is that the system was implemented along Central Avenue, rather than Lomas Boulevard. In short, the decision came down to a few major factors:

- Central is the backbone of the city’s transit network and often had full buses that prohibited expansion on other routes, such as San Mateo.

- At the time, Central hosted the busiest bus routes in the city, so there was a need to improve travel times and service quality along this corridor. BRT along Central would impact and improve service for the highest number of riders as well as increase capacity to allow for future expansion to other corridors.

- Central Avenue is a mixed-use corridor running through the city’s densest neighborhoods, a prime corridor for rapid transit, linking homes to job centers.

- Rapid transit along Central Avenue provides the biggest potential for increasing housing, commerce, and investment in the city.

- The introduction of the ART system also aimed to encourage economic development and revitalization along the Central Avenue corridor, similar to how BRT systems have been used in other cities, such as along the Cleveland Health Line, to stimulate local economies.

- For example, shifting rapid transit to the center lanes helps calm auto traffic while allowing transit to remain fast and efficient, and in doing so, induces people to spend more time (and dollars) at shops and restaurants in Nob Hill and EDo, resulting from a safer, quieter environment.

- Placing ART on Central Avenue aligned with broader City planning goals, such as promoting sustainable transportation, reducing traffic congestion, and enhancing the quality of public transit.

- Travel demand patterns and congestion levels were factors in selecting Central Avenue as the route for ART. Placing the system where there is higher demand and traffic congestion, simply offered more benefits.

Decisions like where to make rapid transit investments are complex and involve numerous considerations. Ultimately, the choice of Central Avenue over Lomas Boulevard for the ART system resulted from a combination of factors that aimed to maximize the benefits for the city, its residents, and its transportation infrastructure.

How ART has Succeeded

Beyond its functional transportation utility, ART has also succeeded in reimagining Albuquerque’s urban landscape. Its design philosophy, focused on safer streets, efficient movement, and pedestrian-oriented streetscaping, has revitalized the aesthetics of the station areas and made Central Avenue a safer and more enjoyable corridor. The incorporation of dedicated bus lanes, sheltered station platforms, and pedestrian-friendly features enhances the overall ambiance, transforming Central Avenue into a more vibrant space that encourages people to walk and explore. Here are just a few of the ways ART has been a success.

Connecting Albuquerque’s Urban Hubs:

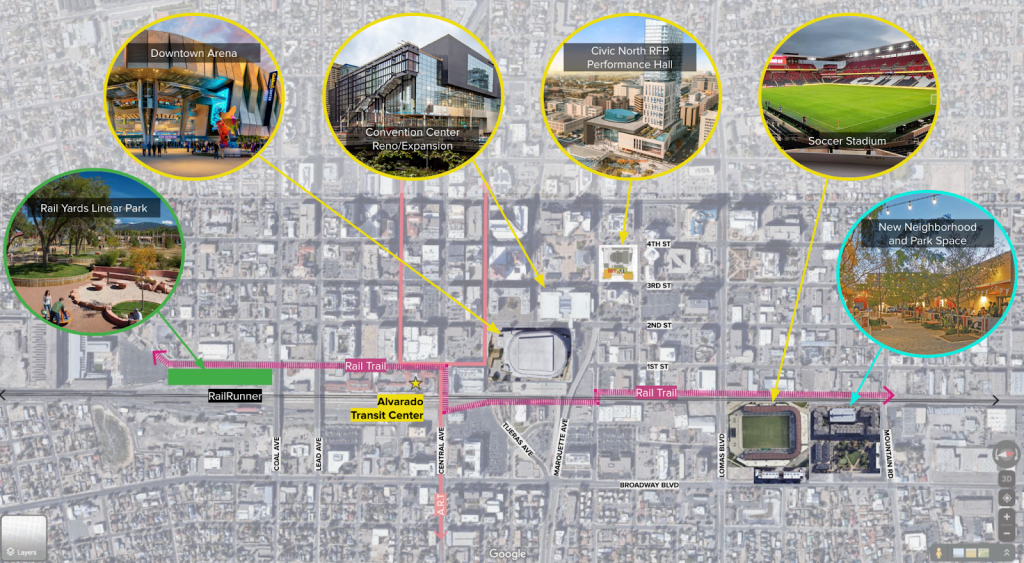

Albuquerque’s cultural richness extends far beyond Downtown, flourishing along the Central Avenue corridor, crafting a vibrant and diverse cultural landscape. While Downtown remains a vital urban destination within this corridor, cultural facilities and captivating locales are scattered across the city’s expanse. The true triumph of ART lies in its remarkable ability to unite Albuquerque’s varied urban centers. As it strings together neighborhoods and cultural hubs, it sparks interactions among diverse populations, forging connections that transcend socioeconomic boundaries. This success serves as a powerful symbol of unity and shared experiences.

What sets ART apart from many other rapid transit projects in the United States is its unique role in bridging both the wealthiest and most economically challenged areas in the region. This connectivity significantly impacts residents’ access to job opportunities throughout the city. At a public meeting about the project in 2014, Tim Trujillo spoke with a resident who lived on the West Side and worked near Sandia Labs who stated that ART and the changes it brought would allow her to cut her commute time in nearly half and spend more time with her family.

With future improvements to the corridor, particularly along the eastern stretches of Central Avenue, Albuquerque is leading by example in promoting urban equity in our country. A transportation system like ART, which serves a wide cross-section of socioeconomic populations, provides a valuable tool for individuals to access enhanced education and employment opportunities, offering transformative pathways toward economic empowerment for all.

A Revolution in Transit-Oriented Development:

As mentioned previously, ART’s alignment was carefully planned to intersect with areas that showed potential for growth. This deliberate approach has spurred transit-oriented development, attracting businesses, residences, and entertainment venues that are located in close proximity to ART’s 21 platform stations. The convenient access to rapid transit is already encouraging new development along the corridor. New multi-family residential developments such as the Broadstone Nob Hill bring in dense, market-rate housing that helps relieve pressure on rent prices while providing residents with transit-adjacent lifestyles.

The City has also worked to create more affordable housing along the corridor, such as the new Hiland Plaza Apartments at Central and Jackson, which will primarily house low-income families. Future developments are already planned to break ground throughout the corridor, including a recently awarded grant to transform the Uptown Transit Center into a dense, transit-oriented neighborhood. Zoning reforms that were implemented in 2016 in anticipation of ART helped bring these projects online, and the potential for further zoning reforms along important transit corridors could help push these improvements further. Ultimately, this growth in transit-oriented development will lead to an Albuquerque with stabilized rent prices, diversity in neighborhood and housing choices, and built-in support for local retail and restaurants.

Lifesaving Pedestrian Improvements and Increased Foot Traffic:

Throughout the ART corridor, project design includes improved streetscaping features such as wider sidewalks, landscaping, benches, public art installations, and pedestrian-friendly crossings. These elements make the station areas more visually appealing and inviting for pedestrians. HAWK signals, which are pedestrian-activated signals that stop traffic for crossing, help prioritize the pedestrian experience and facilitate safer crossings on Central. The improvement in safety is now documented in the data, too, and dramatically at that. Nicholas Ferenchak, professor in the Department of Civil, Construction, and Environmental Engineering and leading the Center for Pedestrian and Bicyclist Safety at UNM, has studied Central Avenue and found ART to have significantly contributed to improved safety on the corridor. In the years since ART has been in service, his research has found a decline of 65% in serious and fatal injuries, mostly due to “lowered vehicle speeds and prohibiting left turns.”

The significance of these statistics extends beyond mere numbers. ART’s impact is particularly profound when viewed through a social justice lens. The neighborhoods served by ART encompass diverse demographics, including many individuals and families who are disproportionately low-income, PoC, refugees, immigrants, and new Americans. In the realm of social justice, concerns have often arisen over rapid transit projects potentially contributing to gentrification, displacement, and inequitable access. However, ART’s remarkable safety enhancements coupled with its commitment to inclusivity challenge these critiques. It stands as a model that demonstrates how public infrastructure projects can be vehicles for positive change, fostering both safety and accessibility while promoting economic equity for all residents, regardless of their background or circumstances.

In areas like East Downtown and Nob Hill, ART has helped create a “Main Street” feel, slowing traffic, and encouraging small business and residential development. ABQ Uptown has attracted retailers with their artificial construction of Main Street-esque facilities. The redesign of Central to accommodate ART allows for neighborhoods along the corridor to compete by leveraging their authenticity as true Main Street neighborhoods. ART provides an alternative to car travel, reducing dependence on private vehicles. As people shift to transit for more of their travel, they are more likely to walk to and from transit stations (and therefore by local businesses) instead of driving, especially for short distances. When combined with the transit-oriented developments mentioned above, we have a Central Avenue primed for human-centered growth and activities.

While ART construction did bring short-term challenges and growing pains, it’s crucial to emphasize the lasting benefits. As seen in cities like Portland, Oregon, during the MAX Light Rail construction in the 1980s, disruptive rapid transit projects initially caused local businesses to close along their routes. However, over time, these projects have been credited with revitalizing neighborhoods and promoting local businesses. Areas like the Pearl District in Portland and the Midtown Exchange in Minneapolis have become thriving urban centers with a strong focus on local businesses. These examples demonstrate that the initial disruption may well be worth it. ART’s long-term vision prioritizes pedestrian-friendly environments, convenient transit, and community vitality. As a result, these neighborhoods are more resilient and authentic, making ART’s enduring impact a compelling success story.

Elevating Sense of Place with Improved Aesthetics:

ART’s design philosophy acknowledges the importance of aesthetics, transforming the streetscape into a more inviting environment. This has created an appealing atmosphere that draws people to explore the area, whether for shopping, dining, or leisure. Decisions to move median plantings and trees to the streetside provide shade and decrease the urban heat-island effect as trees mature. Trees placed along the sides of a street live longer than those placed in the center of the street as in the previous configuration of Central Avenue. With increasingly hot weather resulting from climate change, the provision of shade and cooler urban spaces has become an essential aspect of planning for the future. New lighting was also installed to help complement the visual appeal of the surroundings and the historical nature of the street while simultaneously addressing safety concerns and ensuring that pedestrians can comfortably navigate the area during both day and night.

Finally, ART’s dedicated stations serve as landmarks and neighborhood anchors, with distinctive designs that set them apart from regular bus stops. This helps establish a clear identity for the ART system, making it easily recognizable to passengers, including visitors, and contributing to the system’s overall branding. ART stations offer amenities such as sheltered waiting areas, seating, and real-time arrival information. These features enhance the passenger experience, making the system more attractive to potential riders and encouraging higher ridership.

Through-the-Roof Ridership:

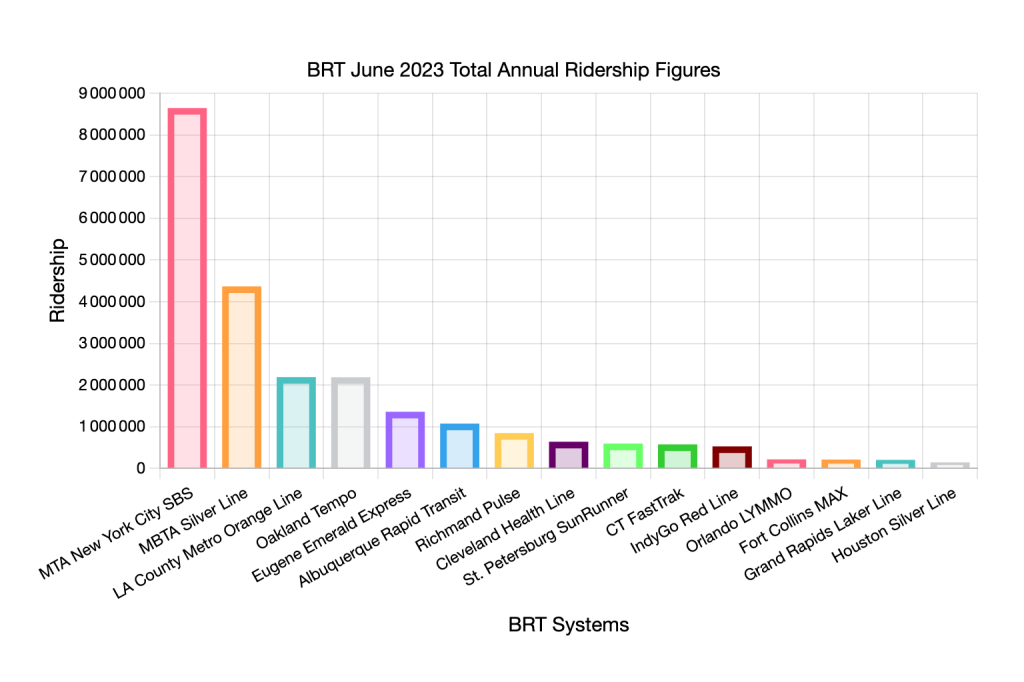

As of June 2023, ART has not only recovered but exceeded its pre-COVID ridership, hitting over a million riders between January and June of this year. This figure placed ART as the 6th busiest BRT in the United States, just behind heavy hitters like Los Angeles Metro’s Orange Line and Boston’s Silver Line. It is actually ahead of Richmond’s Pulse Service, Indianapolis’s Red Line, and even the Cleveland Health Line, which inspired many of the United States’ BRT projects, in ridership (National Transit Database, 2023). With increased ridership continuing, it is poised to continue on this trajectory of success. With recent cuts to ABQ Ride’s regular bus system accounting for a 30% reduction in service for most local routes due to a bus driver shortage, ART’s ability to outperform the rest of the system is a testament to its utility and ability to attract riders. ART’s ridership success is also happening while downtown office vacancies remain high in the aftermath of COVID-19. Having started service only a few months before the pandemic, it is hard to avoid wondering what ridership on ART could be today had it never happened. Despite that, we can now look forward to ART cementing its place within the post-pandemic urban fabric of Albuquerque.

While exceeding pre-COVID ridership levels is a positive sign, continued investment in maintaining and improving the system will be important to ensure its long-term success and continued positive impact on the community. Improving ridership and ART’s success will include future changes to land uses along transit corridors and constructing new ART lines to bring benefits to more of the city while also enabling more people to shift their travel to transit and away from private vehicles.

What Can ART Do for the Future of Albuquerque?

It is important to view ART as a foundational step towards a more comprehensive rapid transportation network. Initial setbacks should be taken as lessons learned, and future improvements and adaptations should be made to optimize the system’s performance and efficiency. In embracing ART, Albuquerque has demonstrated a commitment to sustainability and environmental responsibility. By promoting the use of public transportation, the City is making strides toward reducing carbon emissions and minimizing the environmental impact of individual commuting choices. In prioritizing transit-oriented development along the Central Corridor, ART also works to decrease housing market pressures and create more choices for Albuquerque residents by providing diverse neighborhoods to live in. This is a success that resonates far beyond the confines of city limits, as it sets an example for other communities to follow, particularly other cities in the West that struggle to get projects like ART off the planning table.

The 24-Hour Economy

Soon after being elected, Mayor Keller stated he wanted Albuquerque to invest in its 24-hour economy. One area where Keller and the city council can support the 24-hour economy is in implementing late operating hours for ART. Late-night transit options improve accessibility for individuals who work late-night or early morning shifts, have evening social commitments, or need to travel during non-traditional hours. This inclusivity ensures that the transit system meets the needs of a diverse range of riders. A robust, late-night transit service can encourage people to enjoy nightlife activities, such as dining out, attending events at Popejoy or Downtown, and visiting entertainment venues up and down the corridor. This can boost local businesses and contribute to a vibrant urban environment. Late-night transit can serve as an alternative to ride-sharing services, which are expensive during peak nighttime hours. Like many cities, Albuquerque struggles to bring inebriated driving under control. By providing an alternative to expensive taxis and ride-share services, we can cut down on this dangerous behavior.

As mentioned previously, ART serves as a connection to better employment opportunities for many in our city, and late-night hours would only enhance and expand that access to more people. Serving all three of the major hospital hubs, the University, Downtown, Uptown, and Nob Hill, ART already connects the densest neighborhoods in the city with many of our largest employers. Nurses and custodians working overnight, hotel workers, and restaurant and bar employees would all benefit from later hours on ART. If we care about having a 24-hour economy, ART plays a major part in ensuring we have one.

Improving Dedicated Busways

ART’s dedicated bus lanes are a key component of its success, but there are areas where they can be improved. For example, in sections where ART runs in a shared or dual-directional busway, many passenger vehicles become confused and cross the lane, which can be dangerous. One solution that could be employed on these dual-direction busways is to install short, center-running curbs that are low enough for the buses to straddle, but high enough to direct traffic from side streets from crossing Central Avenue. Examples of this exist on Indianapolis’s Red Line, another BRT project built at the same time as ART. In addition to the bi-directional lanes, ART would benefit from dedicated lanes on Copper and Gold downtown. Though these lanes would replace parking spots, it would help increase speed for ART through the downtown core. A queue jump heading east from 10th Street may also help ART vehicles circumvent congestion that can happen at 8th, Central, and Park, particularly when cruisers are taking to the streets (though recent closures of the roundabout that essentially divide the circle in two have helped alleviate this concern on Sundays).

Future Expansions of ART are Needed

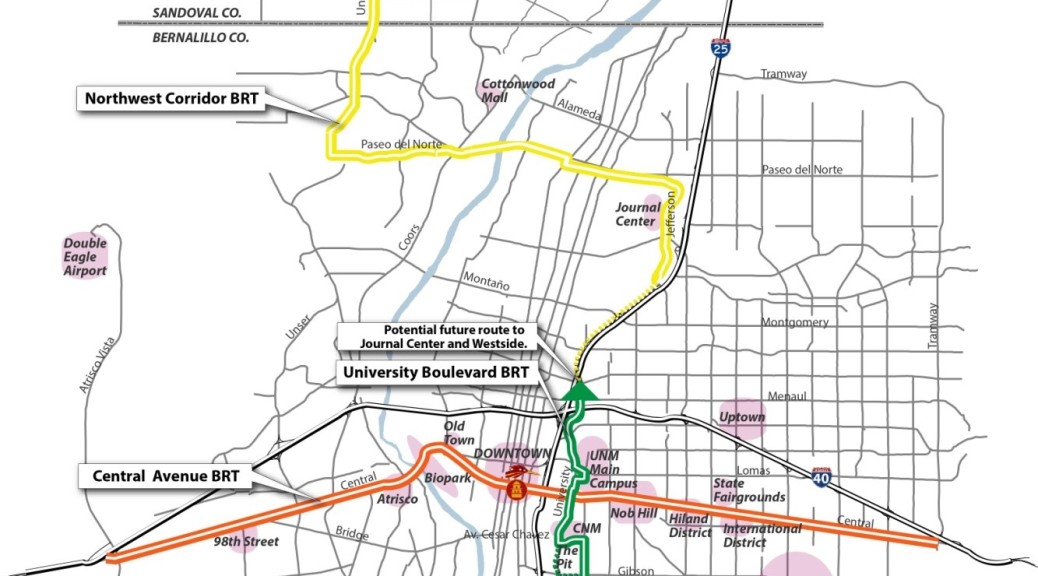

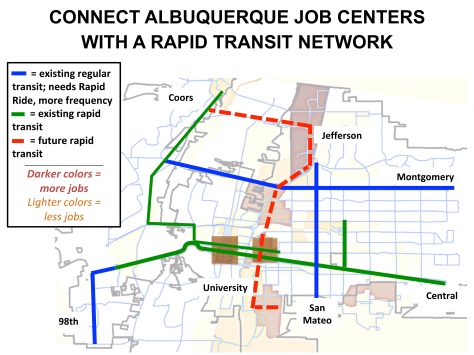

The changes mentioned above are changes that are all readily available to be implemented quickly. But what about further down the line? We have already seen how ART is helping to change land use and increase safety, transport efficiency, and job accessibility. These are not changes that need to be constrained to the present ART Corridor. At present, several important job centers and corridors are absent from ART service, including the Montgomery corridor, much of 4th Street, Cottonwood Mall, and the Journal Center.

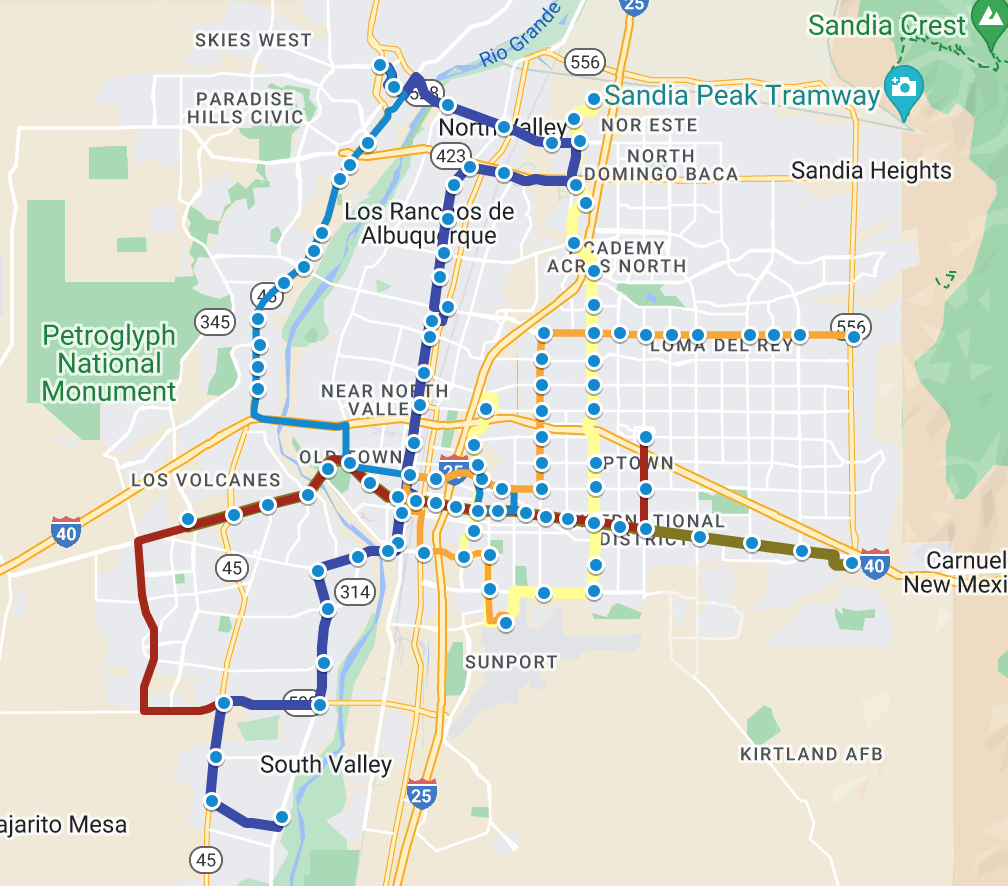

Imagine an ART line connecting the Sunport or Downtown with the Journal Center and the Westside. In addition to these areas, a key restraint to more development of multi-family housing at Mesa del Sol is the lack of high-capacity transit. A common complaint about ART is that Central Avenue already had good transit and that the money should have been invested to improve transit elsewhere. Though we have touched on why it was appropriate to develop Central Avenue first, the heart of the critique IS very relevant. Much of Albuquerque DOES need more investment and there are people who would happily leave their car at home if it was more convenient for them to do so. The City’s “ABQ Ride Forward Initiative” is currently looking at ways to rebalance the bus network so that wider parts of the city would have greater access to frequent bus lines. This is definitely a step in the right direction. However, the initiative is simply a rebalancing, moving around current infrastructure without adding anything new. What would investing more in the transit system look like?

ART Can Catalyze the Creation of “Urban Villages”

With an expanded ART network, we could begin reimagining areas of the city so that amenities, housing, retail, and employment opportunities could be accessed over a wider territory. Creating what are called “urban villages,” mixed-use areas with medium to high density that can anchor otherwise suburban areas, is a strategic approach to fostering sustainable urban development and vibrant communities. In Uptown, we are slowly seeing the district infill with new apartment buildings, hotels, and amenities. Winrock Town Center may very well become a new urbanist infill project, in addition to the Uptown Transit Center being rebuilt as mentioned before. As Uptown slowly becomes an urban center in its own right, we should imagine how we can create urban villages in other areas of the city. Imagine how a rebuilt, enhanced ART Blue Line could help transform the area around Cottonwood Mall. Currently, the Cottonwood Mall area is a crossroads of the West Side, connecting various West Side neighborhoods to nearby metro communities like Corrales and Rio Rancho. It is home to one of the largest high schools in the region and near the Southwest Indian Polytechnic Institute. A new ART line could help densify this area, adding options for employment, entertainment, and commerce, and over time, alleviating cross-river commutes.

The images above paint a picture of how Cottonwood and other areas of the city could be reimagined as new “urban villages,” serving as hubs within sectors of the city. With a good rapid transit system connecting them, Albuquerque would be much better suited to meet the challenges and demands of the 21st century.

Improved Regional Connectivity

If you are a New Mexican living far from Albuquerque with a chronic illness such as cancer, HEP-C or HIV, it is likely that you travel into the city regularly for continued treatments. Albuquerque serves as a regional healthcare and services destination hosting some of the only specialized medical, educational, and business centers in the state. It isn’t uncommon for residents in underserved outlying communities to delay care or other activities due to a lack of transport and means. Good public transit inside the city can help create the environment to better support regional transit as well. As Rio Metro slowly improves the Rail Runner to (hopefully) run hourly throughout the day in the next decade, that could bring additional rider demand into the city. But what do you do once you get to, say, Montaño Rail Runner Station?

An expanded ART could better connect the Rail Runner to regional job and services hubs at UNM Health Sciences Center, Journal Center, Cottonwood, and Sandia National Labs, as well as other areas that aren’t necessarily surrounding a station. Suddenly, a lot of those motorists from Santa Fe, Los Lunas, and Los Alamos who did not want to deal with a 40-minute bus ride or a $20+ Uber have options, lessening congestion on I-25 and improving environmental outcomes. With improved regional bus and rail connections, these benefits can extend to underserved populations, who desperately need fewer barriers to accessing care, education, and opportunities. Many New Mexicans would love to have expanded rail and bus options from Albuquerque and expanding ART can help lay the groundwork to make that possible. As the state’s central hub for just about everything, we can leverage ART to help promote better health outcomes and economic prosperity throughout New Mexico.

Where Should ART Expand Next?

Let us know in the comments below, or reach out to the team at UrbanABQ for further discussion!

*BRT Ridership for Cleveland Health Line reflects passenger numbers as of May 2023.

All photos of ART were taken by the author.